Copyright © 2026 by Greg Wyatt

VAXXED II – They are Still Monetizing Our Story

/1 Comment

They are still monetizing Weston and Emily’s VaxXed Story like the thousands of others. Pathetic human beings doing what they do best.

Health Freedom Summit 2022

/0 Comments

The never-ending grift continues.

Before one ends another begins!

Pay careful attention to the monetizers,

They are always the same.

#MonitizingMisery

Eugenics & America’s Campaign To Create A Master Race (Video)

/1 CommentLucien Howe (September 18, 1848 – December 27, 1928) was an American physician who spent much of his career as a professor of ophthalmology at the University at Buffalo. In 1876 he was instrumental in the creation of the Buffalo Eye and Ear Infirmary.

Howe is mainly remembered for his work in the prevention of blindness. In 1926 he established the Howe Laboratory at Harvard Medical School for research and study of biochemistry, genetics, neurobiology, and physiology concerning the eye. The American Ophthalmology Society names its most prestigious award—the Lucien Howe Medal after him. Howe was a catalyst in New York State for an 1890 statute sometimes called “The Howe Law,” requiring application of silver nitrate drops in the eyes of newborns as a disinfectant to prevent neonatal infection and possible blindness.

Howe was also a major figure in support of the controversial science of eugenics. He believed that eugenics could be a tool in the fight against preventable blindness, specifically the small percentage of cases that were inherited. He theorized that by sterilizing the blind, inherited blindness could eventually be eradicated.

Howe was a member of the International Eugenic Congress’s Committee on Immigration and president of the Eugenics Research Association. The eugenics movement sought to prevent the birth of “defectives” through regulation of marriage, involuntary sterilization, or segregation of potential parents deemed genetically inadequate. Howe supported and helped draft proposed legislation to prevent procreation by people with poor vision and by people whose relatives had poor vision. He even advocated imprisonment of blind people to keep them from reproducing. Howe conducted surveys of homes for the blind nationwide to gather family histories and identify people whose blindness was believed to be hereditary. Howe headed a committee of the American Medical Association, which collaborated with the Eugenics Record Office to register family “pedigrees” of blind people.

Leaders of the eugenics movement such as Harry Hamilton Laughlin regarded Howe’s eugenics campaign against blindness as an opening wedge for a far more ambitious eugenics agenda, paving the way for broader measures against the birth of other babies with inherited “defects.” Howe and his eugenicist colleagues sought to craft legislation that would pass constitutional muster. They believed that blindness, as a hygienic trait, would be an easier target for eugenics legislation than such “defective” traits as “feeblemindedness” or a family history of poverty.

Howe’s own eugenics activism targeted more than blindness. He also proposed requiring a large cash bond from any marriage license applicant suspected of being “unfit.”

Harry Hamilton Laughlin (March 11, 1880 – January 26, 1943) was an American educator and eugenicist. He served as the Superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from its inception in 1910 to its closing in 1939, and was among the most active individuals in influencing American eugenics policy, especially compulsory sterilization legislation.

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity research from 1910 to 1939. It was established by the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Station for Experimental Evolution, and subsequently administered by its Department of Genetics.

Both its founder, Charles Benedict Davenport, and its director, Harry H. Laughlin, were major contributors to the field of eugenics in the United States. Its mission was to collect substantial information on the ancestry of the American population, to produce propaganda that was made to fuel the eugenics movement, and to promote the idea of race-betterment.

Robert Mearns Yerkes (May 26, 1876 – February 3, 1956) was an American psychologist, ethologist, eugenicist and primatologist best known for his work in intelligence testing and in the field of comparative psychology.

Yerkes was a pioneer in the study both of human and primate intelligence and of the social behavior of gorillas and chimpanzees. Along with John D. Dodson, Yerkes developed the Yerkes–Dodson law relating arousal to performance.

As time went on, Yerkes began to propagate his support for eugenics in the 1910s and 1920s. His works are largely considered biased toward outmoded racialist theories by modern academics.

My Favorite Research Tool

/5 Comments

Five years ago when I began noticing that many people in “The Movement” were off, to say the least, I started looking at them more closely. This was just one of the websites I used to discover the truth and it is a good place to start:

Many more posts coming on this software along with actual examples of what can be found on these shysters. Remember this is “Public Information” that anyone can access to uncover the truth.

Prepare to be shocked.

#underthebus #monetizingmisery

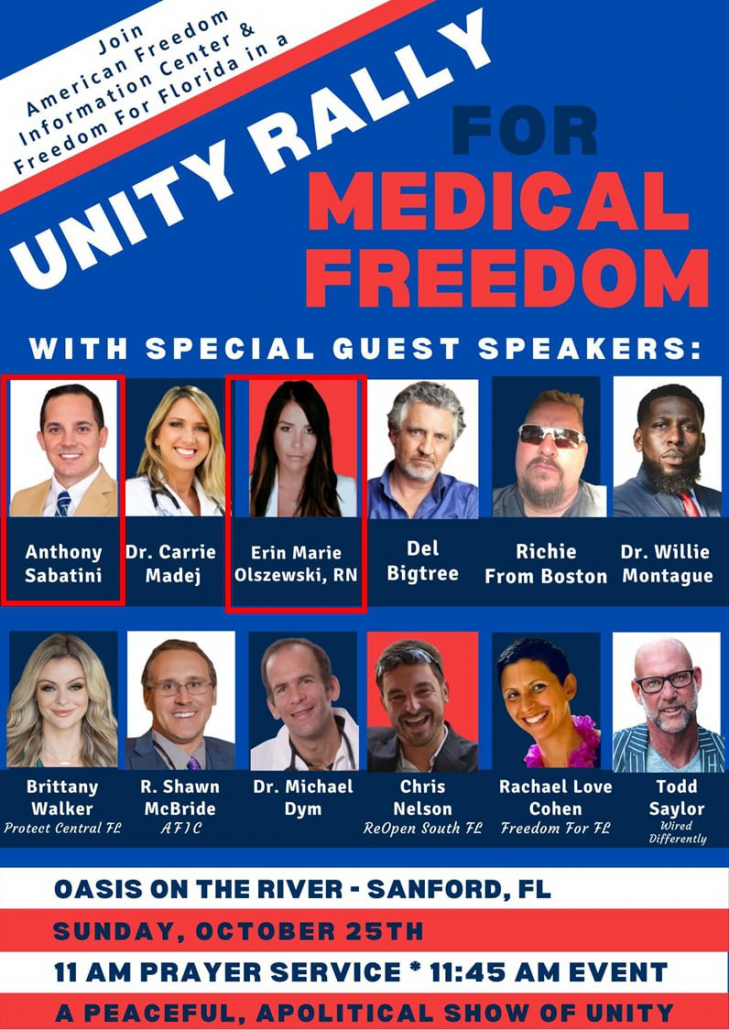

Unity Rally – The Usual Players

/1 Comment

At this point, the re-occurring theme should be fairly obvious.

Kevin Tuttle Connection to the USDA and GMOs

/2 Comments

It appears Air Force Public Affairs Officer Kevin Tuttle-Evenpinah worked for the USDA and at the same time had an interest in GMOs, too!

Is it a coincidence he worked for a vaccine insert translation company when his interest shifted to vaccines?

What a coincidence!!!

#InVinoVeritas

#CaptToodles

Source: https://t.me/co_appleseed

Menthol Prohibition?

/3 CommentsPsaki says menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars will be prohibited to “significantly reduce tobacco-related health disparities.”

No, they did it because menthol cigarettes prohibit the Spike Protein from attaching to the ACE2 genes, meaning it won’t replicate.

This is a bullshit coverup right here folks.

Psst, smokers aren’t getting convid in any big numbers.

Patents, Patents, Patents…

/1 Comment

How is it that all these supposed wild diseases are patented??? Doesn’t that mean they created them?